Published: 17 March 2014

written by Dave and Bonnie Sanders

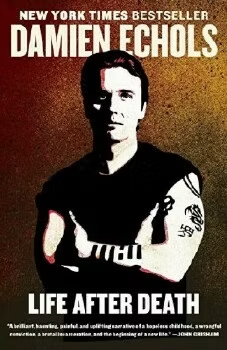

In Life After Death (2012), Damien Echols of the West Memphis Three reveals much about a troubling aspect of our nation’s criminal justice system. Despite overwhelming evidence of his innocence, the Attorney General of Arkansas wasted precious time, state funds, and taxpayer money to “defend a corrupt trial” and keep Echols in prison. Echols states:

The statement they released to the media says it’s their constitutional duty to defend the guilty verdict. Perhaps I’m wrong here, but I thought their duty was to defend justice. p. 369

In fact, a prosecutor’s mission should be a balanced one: convicting the guilty and protecting the innocent. When convicting the guilty is prioritized over protecting the innocent, wrongful convictions are inevitable.

So what causes the scales of “justice” to tip toward conviction? Why do prosecutors spend thousands of dollars fighting to keep people behind bars when there is convincing evidence of their innocence? Why are some prosecutors so reluctant to admit a mistake – even when that mistake was made by prosecutors before them? (For an infuriating example of such prosecutorial stubbornness, please see the case of Lorinda Swain.)

A simple answer to these questions does not exist. Some prosecutors – like persons employed in any profession – are just “bad apples.” They engage in unethical conduct for personal gain. For instance, they may be intent on winning convictions because convictions win elections. They may conceal new exculpatory evidence to protect their fragile egos.

But the problem is bigger than bad apples. The lack of an effective system to hold wayward prosecutors accountable shows us that the whole barrel is rotten. Prosecutors – unlike persons employed in other professions – are rarely held accountable for wrongdoing, whether their actions are unintentional or conducted with malicious intent. As the Center for Prosecutor Integrity reports, “Fewer than 2% of cases of prosecutor misconduct are subject to public sanctions, and when they are imposed, the sanctions are often slight.” If we want to decrease the number of unjustified prosecutions, then we need to hold prosecutors accountable for their actions.

The good news is that problems of prosecutorial abuse and misconduct are finally getting the attention they deserve. In part, this attention is the result of efforts made by the Center for Prosecutor Integrity, which has created a Registry of Prosecutorial Misconduct (see http://www.prosecutorintegrity.org/.) The hard data provided by the registry can increase our understanding of this disturbing phenomenon and eventually lead to strategies for increasing prosecutor integrity – which ultimately will lead to fewer wrongful convictions.

Comments